The Strategy of Indirect Approach

Noted British military strategist B.H. Liddell Hart was a proponent of what he called the Strategy of Indirect Approach. The idea is that if you attack the main objective directly, the enemy will likely be prepared with strong entrenched forces to fight back and defeat you. If instead you sneak around the edges of the main objective, you can weaken the enemy's position and eventually capture it with far less bloodshed. Following Sir Basil's advice, I've been wiring this car by doing a lot of jobs that, strictly speaking, are not actually wiring.

This slow process of 'preparing the battlefield' is always frustrating and either the media talking heads (in the case of actual military operations) or the voices in my own head (in the case of Ill-Advised Sports Car Projects) say, loudly and repeatedly, that nothing is being accomplished. However, if done correctly, this phase can lead to what feels like suddenly accelerating progress.

The Last of the Indirect Operations

One of the ongoing stumbling blocks has been figuring out where to put the ECU, fuse box, and relays box. I knew I wanted them behind the passenger side dash - so general location known - but exactly where and exactly how to install them has been difficult to visualize. Every idea I came up with was either going to be very awkward to wire in the first place, or very awkward to access later, or both.

So I worked around the periphery of the problem and narrowed it down and then got a very timely bit of advice from the blokes on the Facebook LMR-141/Replicar page which was to put everything on a drop-down panel.

It took me an evening and most of a Saturday to get this (hopefully) last of the non-wiring wiring jobs done, but as I worked through it a lot of other questions answered themselves. A particular advantage is that I can now do the intricate wiring that goes between the fuse box, ECU, and relay box with the panel sitting on my electronics workbench. Not only do I have better light, better visualization, and a better seating position, I also have air conditioning - which is decidedly nontrivial in the middle of an unseasonable heat wave. And when it does come time to re-mount the panel in the car and wire it in to everything else, I'll be able to work from above instead of having to crawl into the passenger side footwell.

Above: bulkhead added to keep iffy heater core plumbing separate from the electrics. Because I am better at wiring than plumbing, and electricity and water are not friends.

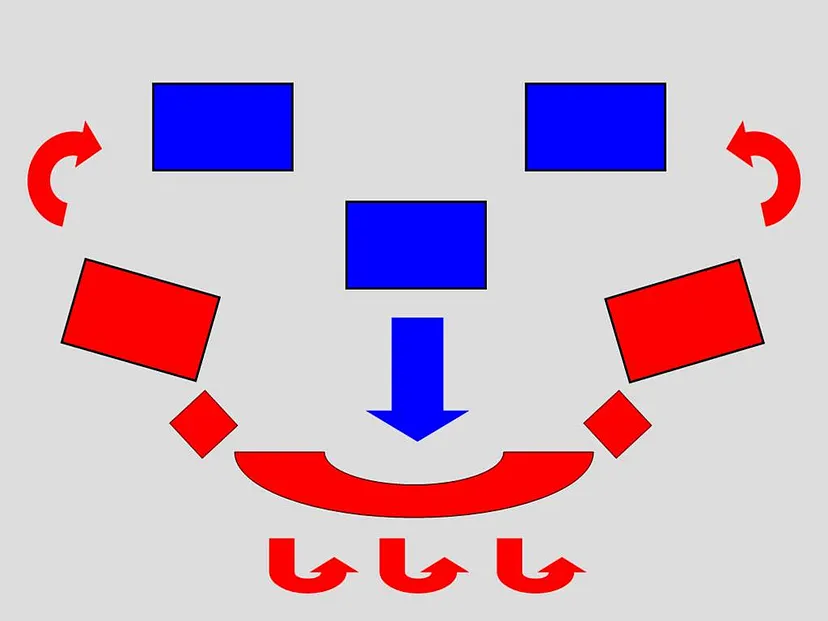

I am continuing to encounter wiring puzzles that require looking things up on the original Miata schematics, drawing my own schematics to sort my thoughts, Googling, or asking for help on web forums. Above left is the OEM fuel injector wiring harness, lined up with cylinder one to the right and cylinder four to the left. You can see that the cylinder 1 and 3 injector trigger wires are yellow with a black stripe, while 2 and 4 are solid yellow. So this would translate into the wiring diagram above right. But this doesn't make sense with the firing order: it looks to me like cylinder 3 would get a squirt of fuel at the same time as 1 (which fires first), then get no fuel injected into 3 when it fires. I have posted this on the various forums and gotten conflicting answers.

The reason I ran into this issue in the first place is that the OEM Mazda harness powers all four injectors from one wire, while the Microsquirt wants injector bank 1 and bank 2 to have separate power supplies. This in turn requires making a new fuel injector wiring harness, which requires understanding how the injectors are wired. The temptation is to wire it the way Mazda did, but I'd like to have a definitive answer before proceeding. Will post an update when I find out.

Above is Wiring Puzzle #2. "Charge 1.4W" is the light that comes on when the alternator is not fulfilling its life purpose of keeping the battery charged and is therefore experiencing existential distress. This seemed like a useful warning light to have, so I put one on my dashboard which was an opportunity to use another one of those cool 1950s jewel lights (below, right). But what are those two resistors in parallel with the charge warning light? Why are they there? Why did they use two in parallel rather than the equivalent single resistor? Can I assume that Mazda is using the traditional schematic symbol for resistors to actually refer to resistors? Do I even know if the world around me is an objective reality? And if there is a world around me and those are resistors, what should their value be in Ohms?

So to sort these things out I consulted Andy the Philosopher-Engineer. He advised me not to worry about the reality or unreality of reality, hypothesized that the resistors are there to prevent overcurrent from burning out the lamp, and suggested I put a 100 Ohm resistor in parallel with the lamp. Then by way of experiment I tried to find the spot on the instrument cluster PCB corresponding to the two resistors, which caused an instant headache (see picture above, center). But then I had the happy idea that if I measure the resistance across the bulb socket (above, right), this would give me the net value of the two resistors (real engineers refer to this as "a keen grasp of the obvious"). Having had this epiphany of the very elementary I measured the resistance at 88 Ohms. So Andy's off the cuff guesstimate was extremely close to what Mazda used (within the tolerance range for cheap resistors). There is also a diode between this and the alternator, so I wired one of those in as well. It would have been easier if I did all this when I wired the dash, but at least I didn't wait until the dash was completely wired in to the car.

Above left is another entry on the "handy tools to have around" list - soldering pliers. Especially helpful when splicing two wires together, or when soldering anything on to the end of a wire. There is a big debate over whether wire connectors should be crimped or soldered - so of course I am doing both.

In summary, I have moved from working on "wiring" to actually working on the wiring. Using Liddell Hart's strategy, I have attacked all around the wiring job and undermined its defenses. Now I am starting my final assault on the main enemy position. And just like Sir Basil professed, this strategy is now resulting in more progress with less toil, tears, and bloodshed. Not entirely without bloodshed, though. As the picture above attests, I always seem to have a collection of dings and scratches in various stages of freshness or healing. Pops Racer's term for this is "idiot rash."

Comments

Post a Comment